The troubled history of Les Halles district in Paris is about to enter another chapter with the imminent completion of the new building designed by French office Berger & Anziutti.

Almost forgotten, a powerful ‘absolute architecture’ project stood out in the 1979 competition, just 8 years after the original Les Halles by Baltard were demolished. It was the entry by Italian architect Antonio Monestiroli, described as follows:

Competition for the district of Les Halles

Paris 1979with Paolo Rizzatto

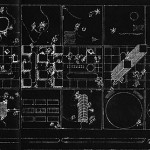

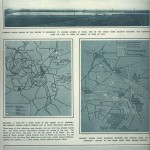

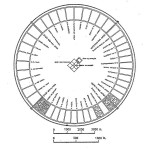

coll. Joseph Campanella, Elizabeth Hammond, Cristina Manzoni, Joy Siegel, Jeffrey StarckThe great void determined by the demolition of Les Halles, destined to be a park, is an opportunity to think about a different city where the road layout has not the role of generating element of urban form but where such a role is assumed by the system of relations between urban elements and natural spaces. In the park, on the opposite side of the existing Bourse, the project involves the construction of a congress building, a new construction that defines the boundary to the east of the whole system. The resulting shape is that of a place between two sides and between two parallel urban public buildings, one old and one new. The park is entrusted with a dual function, that of being a place for buildings to overlook and a place of knowledge of the city that surrounds it.

Paolo Rizzatto, principal architect on this project, adds:

The area is bordered on the short sides by two public buildings, an ancient and a new one, and on the long sides by two residential buildings with interruptions where the urbanization behind is worth seing. All this happens in a place where the north and the south edges exist and have relations one with the other. The lawn in the middle becomes the place where these relations take place, the place from which both new and existing buildings can be seen and where the urban tissue reflects and reconnects.

Here follows an excerpt from: “Reinventing Architectural Monumentality”, an article by François Claessens on Oase 71 (available here in pdf)

The Architectural Representation of Urban Life

The Italian architect Antonio Monestiroli – who previously worked with Rossi – has attempted to investigate how architecture could be used to represent urban collectivity in the contemporary city. In doing so, he distanced himself from Koolhaas’s position and at the same time tried to take Rossi’s theory of the city a step further. Monestiroli’s studies concern not only peripheral areas round the existing city, but also sites within the historical city that have become vacant as existing buildings and their functions become obsolete and old industrial sites and railway yards are abandoned. His urban projects are essentially developments of the ‘open’ city model, which stands in a dialectical relationship to that of the ‘closed’ city.12 The closed city – usually identified with the traditional, historical form of the city – is clearly marked off from the surrounding landscape, whereas the modern, open city is marked by a constant interpenetration of urban and landscape elements. The closed city is made up of a system of pieces of land bounded by streets: urban blocks. However, this system

was abandoned in city districts that were built after the Second World War. According to Monestiroli, the urban block was no longer the basic structural element in the city, and the pattern of streets was no longer the generator of urban form. Yet no powerful new elements arose in their stead. The resulting open city was based on a contrast between urban elements and the surrounding countryside.In the open city model, urban blocks bounded by streets made way for urban islands surrounded by countryside. The paradigm for this model can be found in Le Corbusier’s Unité, which offered a new way of understanding urban elements and how they were interrelated, and above all how they related to the countryside. Yet Monestiroli found that, despite the clarity of this concept, no sufficiently stable model that might indicate a way of building the open city had developed since its emergence.13

Thus, as Monestiroli saw it, the object-like archipelago model favoured by Koolhaas did not provide a definitive answer to the question of the open city. Monestiroli’s research into a new relationship between city and country, between urban elements and the natural landscape, was based on a clear principle, namely ‘that the form of the place stems from the system of relations established between distinct urban elements’.14 A key initial step in all projects is to bring the countryside back to the vacant sites as a new setting for the project. The natural landscape is the foundation, the stage on which the urban elements can be presented: ‘In this new context is defined the form of the place, as established by the architecture of the single buildings and the relations between them.’15 The natural foundation for urban composition that Monestiroli introduces in his projects is the lawn.

The lawn, which serves as an image of the countryside, functions as an organising field in which the structures are related to each other. It is the common element that links up the individual buildings. ‘What matters is not so much the quality of the individual buildings, built by different architects in different periods, as their arrangement and reciprocal relations. What matters is the form of the central place . . . . In that place the city represents itself.’16 The composition of the buildings on the lawn defines a place in the city where public institutions are combined into a recognisable whole. The lawn provides a new context for the architecture of the public buildings to stand out against.17

Unlike Koolhaas, to whom the space between buildings is simply a void, ‘non-architecture’, Monestiroli focuses on the relationship between the objects and the architectural definition of the space between them. What concerns him here is the representation of urban collectivity. The city is a form that represents our way of life, a collective experience par excellence: ‘The house, the schools, museums and theatres the architect built are for all the citizens, and in their form the citizens ought to be able to recognise not so much the talent of the person who made them, but their own culture, the fundamental motives of our lives . . . Perhaps we can say that this is the objective of all architecture, that of expressing the life that takes place inside it.’18 Espousing the view that architecture is a way of designing daily life entails a moral, political choice, and one with architectural implications. Those who design the city – the environment in which people live their daily lives – must be aware of their collective responsibility. This means that architects cannot simply design ‘their’ buildings for their own glory, or that of their clients. It is also, or perhaps even primarily, their duty to build for the city and the urban community – and this responsibility must be reflected in their choice of architectural forms and in the way they shape urban space. Translation: Bookmakers, Kevin Cook

Notes:

12 A. Monestiroli, Temi urbani. Urban Themes, Milaan 1997.

13 Ibid., 63-67.

14 Ibid., 67.

15 Ibid., 68.

16 Antonio Monestiroli, The Metope and the Triglyph. Nine lectures in architecture (Amsterdam, 2005), 127 ff. (Originally Rome-Bari, 2002).

17 Ibid., 133.

18 Antonio Monestiroli, ‘Research by Design’, in: M. van Ouwerkerk and J. Roseman (eds.), Research by Design. Proceedings A (Delft, 2001), 41-46.

The following is a collection of study sketches made during the competition, from the archive of the Centre Pompidou. (© Philippe Migeat – Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI (diffusion RMN) and © Paolo Rizzatto)

Leave a Reply