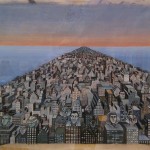

In 1975 New York Magazine (Oct 20. 1975) published an article by Dorothy Seiberling summarizing, by means of a hypothetical journal, the crucial events of the American Revolution as the spotlight was in the territory of Manhattan. The accompaning illustrations (born out of the joint work of photographer Henry Groskinsky and painter Julian Allen) reimagine how the Battle of Manhattan might look if it happened today.

The original article with the illustrations is available on Google Books.

This piece somewhat reminds us the literary experiment by our friend Leopold Lambert, who has reimagined the events of the Paris Commune as if they happened in contemporary New York. (“Official report on the question of the so-called New York Commune“).

The Battle of Manhattan

By Dorothy Seiberling Paintings by Julian Allen/Photographs by Henry GroskinskyFrom 1775 to 1776, the spotlight of history lit up New York. This is how it might look if the Revolution happened here today.

If you think New York is about to go down the drain, consider its predicament 200 years ago: it was about to go up in smoke. From midsummer of 1775, guns of two British warships were continually trained on the city from the East River, ready to hurl a thunderous rain of fire on the 25,000 citizens and their highly flammable buildings. To add to the peril, American patriots —or “factious offenders,” as they were labeled by some New Yorkers— were flagrantly provoking the British by looting military supplies from the king’s warehouse near East 48th Street, capturing a British boat and its crew in Turtle Bay, and even plotting to kidnap Lord Tryon, the royal governor of New York Province.As if that weren’t trouble enough, New York had its “image” to contend with. In 1775, scarcely a man or woman was alive—in the rest of the colonies, that is—who didn’t regard New York as Sin City. From Maine to Georgia, Americans were suspicious of that headquarters of hedonism on the Hudson, with its polyglot population, its strong leanings toward the Old World —in a word, its un-Americanism. Many in the colonies would gladly have seen it lopped off and shoved out to sea.

But the nuisance of it was, it was so strategic; the harbor was unmatched and large ships could sail more than a hundred miles up the Hudson. The British determined to control New York; Washington hoped to thwart them. So as 1775 drew to a close, the spotlight of history swung into position over New York and, for a few frantic months in 1776, lit up its streets, pastures, swamps, and hills from the Battery to the Bronx. Then, on a bleak day in November, the British overwhelmed Fort Washington and the Battle of Manhattan was over.

In New York the scars of the Revolution have long been superseded by other blights and blemishes—as well as blessings. But though the sights have changed, many of the Revolutionary sites retain their historic names, reminding us where the action was. The pictures on the following pages show what would be happening where if the Battle of Manhattan took place today.

August 23, 1775

Hijacking the Battery Guns

To bolster fortifications up the Hudson, New Yorkers steal British cannons from the Battery and haul them up Broadway, as the royal battleship ‘Asia’ bombards the city from the East River.

Soon after George Washington was named commander-in-chief of the Con-tinental Army in June, 1775, serious planning got under way to prepare for a possible full-fledged war with the British. Translating plans into action, however, was not easy, for the colonies were disorganized and even staunch supporters of the American cause hoped for a negotiated settlement with the British. Still, defense of strategic areas was essential, and one such area was the Highlands, the high ground above the Hudson River between Peekskill and West Point. A battery of guns placed on each side might block the British Navy if it tried to move on Albany. The Continental Congress entrusted New York with the fortification of the Highlands, but throughout the summer little was done. Finally, on August 22, when a scant quorum showed up for the regular meeting of New York’s Provincial Congress, a notorious Son of Liberty named Isaac Sears —instigator of the plot to kidnap the royal governor— moved that a subcommittee be empowered to “liberate” the British cannons at the Battery

and install them in the Highlands. Since most of the conservative members of the Congress were absent, the motion passed and Operation Hijack got under way.Near midnight on August 23, a contingent of New York soldiers took up positions along the edge of the Battery facing the water, to watch for any action from British ships and to conceal the heave-and-hauling going on behind their backs. Twenty-one naval guns mounted on small-wheeled carriages and weighing at least a ton had to be wrestled off the ramparts, and the New Yorkers—including young Lieutenant Alexander Hamilton— struggling with ropes, dragging and shoving the massive cannons up the incline of Broadway toward Wall Street, cursed and shouted enough to alert the whole town, not to mention the British —who, in fact, had been tipped off to the plan but were apparently doubtful it would be executed. A sloop from the battleship Asia was sent in close to the flattery to keep an eye on the proceedings, but for an hour or more, its sailors made no move. Then a musket was fired, the Americans returned a volley, and a steady exchange of shots ensued as the sloop headed back toward the Asia. Suddenly there was a sonorous boom, followed by rounds of grapeshot—the Asia had spoken. New Yorkers leaped out of bed and into the streets in panic. Alarm drums began to beat, militiamen rushed to their stations, and citizens every-where bolted—some to their cellars, some to the ferries and highways lead-ing out of the city. The cannon brigade had managed to pull almost a dozen guns as far as City Hall Park (then called the Commons) when the Asia let go again with a 32-gun broadside that reverberated throughout the city, tore through the roof of Fraunces Tavern, and damaged a row of buildings on Whitehall. Operation Hijack came to a stunned halt.

July 9,1776

Toppling the King

After hearing the Declaration of Independence read aloud by Washington side, defiant citizens pull down the statue of George III in Bowling Green.The Glorious Fourth, for New York, came five days late. At the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, New York’s delegates were under orders to abstain from voting on any resolutions until New York’s Provincial Congress could consider them. So the Declaration of Independence was adopted on July 4 by only twelve colonies. New York did not receive copies of the Declaration until July 8, and did not vote “yes” until the following day.

Washington, who was then headquartered in the city, dispatched copies of the Declaration to every brigade in the area and ordered it read aloud so that “this important event” would provide “a fresh incentive to every officer and soldier to act with fidelity and courage….” Washington himself rode over to the Commons, where a crowd had gathered for the ceremonies. Sobered by the occasion and the prospect of war at their doorstep -Staten Island had just been seized by General William Howe- the crowd drifted down to Bowling Green. Suddenly there was a commotion. Some men had climbed atop the gleaming equestrian statue of King George III in the middle of the Green and were lashing ropes about the royal torso and wedging crowbars under the prancing mount. In no time the statue was toppled from its pedestal, breaking into massive pieces. Then, men fell to with axes and hammers, further dismembering the kingly effigy so it could be carted off and melted down for guns and bullets.

August 29,1776

Escape From Long Island

After a mortifying defeat by General Howe’s army, Washington extricates his battered troops from Brooklyn and ferries them to safety in Manhattan.General Howe lost little time in giving the upstart states a heavy dose of war. On August 22, he landed 20,000 men at Gravesend Bay in Brooklyn and a few days later launched a maneuver which devastated the American forces, caught between Prospect Park and the intersection of Fulton and Flatbush avenues. Some 1,300 Americans were captured, killed, or wounded. It was a humiliating defeat for the fledgling Continental Army.

The day after the disaster, while Howe was inexplicably resting on his laurels, Washington ordered to Brooklyn a regiment of Nantucket fishermen and every small boat in the vicinity. On August 29, as night fell and heavy rains whipped the makeshift fleet, an orderly procession of the well and the wounded converged on the Brooklyn shore near the foot of Fulton Street. All night long the boats ferried soldiers to Manhattan without raising the suspicions of the British. Only a rear guard remained to be evacuated when dawn broke. Miraculously, a dense fog drifted over the river, cloaking the escape of the last soldiers and Washington himself.

September 16,1776

Invasion of Manhattan

The British soften up Manhattan with a massive bombardment before landing troops at Kips Bay.Though Manhattan was now perilously exposed, Washington determined to regroup his forces and make a temporary effort to defend it. Soon after he deployed 5,000 soldiers along the East River, the British sailed five men-of-war up to Kips Bay. On Sunday, September 15, they lay offshore near East 34th Street, bow to stern, concealing 80-odd flatboats filled with 4,000 British and Hessian soldiers. At 11 A.M., 86 naval guns let loose with a bom-bardment that soon drove the Amer, cans out of their trenches along the embankment and up Murray Hill toward safety. By the time the flatboats unloaded their troops, all stations were deserted on the Kips Bay front.

September 15, 1776

Rout at 42nd Street

When the British land at Kips Bay, American troops take to their heels. Washington tries to rally them, but even his rage fails to halt their flight.Two hours before the British began bombardment of Kips Bay, Washington set out from his quarters in the gracious Morris-Jumel Mansion overlooking the Polo Grounds and headed south to check up on enemy movements and the disposition of his own troops. By the time he reached Harlem, he was “saluted” by the first of the 86-gun British broadsides. Washington broke into a gallop. He wasn’t sure where the action was, although he could see that 125th Street, where he expected a landing—the British had recently occupied Randall, Island—was basking peacefully in the morning sun. He headed toward Lexington Avenue hoping to get a clearer view of the lower East River. A one o’clock helicopter report would have clued him in on one of the most chaotic traffic scenes in the city, history. Connecticut recruits were scrambling out of their ditches at Kips Bay and heading west; regiments to the south, catching a glimpse of the British redcoats and the Hessians’ blue- and green-coats, took off in all directions. By the time Washington got to 42nd Street, his army had disintegrated into a rabble on the run.

Except for two brigades. Their officers had managed to march them uptown in military order. They arrived at 42nd Street at about the same time as Washington. Stunned by the rout he had witnessed along the way, the general still hoped to make a stand near the crossing at Fifth Avenue. He ordered the two brigades to take up positions behind walls and fences. The soldiers hesitated. It was all very well to keep ranks when marching away from battle, but to join battle, that was something else. Abruptly the men took flight.

Washington whirled on his horse. He berated the fleeing soldiers, shouting commands— “Take the wall, take the cornfield”—to no avail. In a rare burst of uncontrolled rage, Washington hurled his hat at the vanishing troops, cursing their cowardice and flailing in all directions with his riding crop. Gradually his rage subsided; the general slumped in his saddle and stared dejectedly at the ground. His aides watched him anxiously, but he didn’t move. Finally, one took his bridle and led the commander-in-chief away.

September 16, 1776

Taste of Victory In Harlem

Washington’s troops lead the British into a partial trap and force them to withdraw from West 120th Street.

After the invasion at Kips Bay, most of the fleeing American soldiers coalesced at the main encampment above 135th Street. Though they were strong in numbers—some 10,000 men—they were demoralized—and ashamed.But there was one outfit, known as the “Rangers,” that was raring to go after the British. All volunteers, they had been hand-picked for Colonel Thomas Knowlton, a hero of Bunker Hill, and when the colonel gave the order to steal down upon the British at daybreak, his men leaped into action. Near 106th Street and West End Avenue, enemy pickets opened fire. As 400 British reinforcements hurried up to the “front,” the Rangers stood ground, firing their unwieldy muskets as fast as they could load them. Not until the awesome Black Watch regiment arrived with bagpipes bawling did the Rangers retreat.

Around 9 A.M., a British bugler blew a familiar refrain—the fox-hunter’s tune signaling that the fox had gone to cover. Demoralized though they were, Washington’s troops felt insulted. He recognized their mood and determined to take advantage of it. He ordered one brigade to march noisily head-on toward the British. Meanwhile, Knowhon’s Rangers and three other outfits were to move quietly east in a flanking action.

The plan worked perfectly—almost. The British rushed to meet the frontal brigade. The flanking party swung unseen around to the rear. But near 123rd Street and Amsterdam, someone mistakenly gave the order to fire. The battle was on. Knowlton climbed onto a ledge to direct his men and was shot in the back—he died an hour later—but the Americans moved forward with such zeal that the British fell back to 120th Street and Broadway. There they reassembled in a stalwart line. The Americans formed an opposing line a short distance away and for almost two hours they traded fire. Then, curiously, though they far outnumbered the 2,000 Americans, the British began to give way. At last the Continental Army was sniffing success – but they were also sniffing empty gun barrels. Their ammunition was almost gone. Washington, suspecting that Howe was sending up more troops, ordered retreat, but for the first time in the New York campaign, American soldiers marched off the field of battle with heads held high.

November 16, 1776

The Fall of Fort Washington

Howe surrounds the fort at the top of Manhattan and, as Washnigton watches helplessly from New Jersey, forces the Americans to surrender.From the Battle of Harlem Heights, it was all downhill for the American defenders of Manhattan. Though the British were plagued with arsonists (Nathan Hale was hanged as one on September 22), the redcoats succeeded in shifting the war into Westchester and tying up Washington’s troops on several fronts. Not until November did they head back toward Manhattan.

Washington recognized that Howe was out to conquer Fort Washington, which commanded a hill at 183rd Street overlooking the Hudson River. By knocking out the fort, Howe would complete his control of Manhattan and be strategically poised to strike at New Jersey. Fort Washington was little more than a crude, though mammoth, five-sided earthwork. It had no outside moat or inside shelter, and no storage for food and water. But General Robert Magaw, who was in charge of the 3,000 men defending the fort, insisted he could hold firm for at least a month.

Magaw’s assurance was soon put to the test. On November 15, Howe sent 30 boats up the Harlem River and dispatched an ultimatum to Magaw: Surrender. Magaw refused. At dawn, Washington descended the hill from Fort Lee in New Jersey and climbed into a boat. As he was being rowed across the Hudson toward Fort Washington, a mighty bombardment lit up the dull November sky. Howe’s ships were blasting the fort from the Harlem Rive, 3,000 Hessians were moving south from the Bronx: and another force was advancing north from Central Park. Washington spurred his oarsmen, then hurriedly climbed up to the fort. There he found Magaw still determined, though less confident. Filled with gloom, Washington returned to Fort Lee and waited. By mid-afternoon it was all over. Magaw surrendered to the Hessians, and the captive Americans were marched down Broadway to prison ships in the harbor. The Battle of Manhattan was over and Washington would not see New York again until December 4, 1783, when he arrived at Fraunces Tavern to bid his officers a fond but soldierly farewell.

Images and text © New York Magazine.

Via: Mika Savela

Leave a Reply