We usually don’t accept text contributions for SOCKS, but we made an exception for this article on the Charterhouse in Padua, Italy featuring original photos and submitted by the two young Italian architects and engineers Marco Lumini and Alberto Michielotto. We feel that the subject (which we are very interested in) and the writing posture, thorough, descriptive and focused on the architecture of the Charterhouse, would fit well within the format and the spirit of our website.

We wish indeed to thank them for their kind and valuable contribution.

The Charterhouse of Padua, a Forgotten Place

Photos by Marco Lumini and text by Alberto Michielotto

Not far from Padua, along the Brenta river bank, stands an architectural complex that, even just by virtue of its bulk, exerts a gravitational pull on those who happen to pass by it, unconcerned about the private property signs affixed all around. Vegetation intertwines together with its capitals, covering its long walls and invading its passages barred by big, rusty padlocks. The Charterhouse of Padua was built starting from the 16th century under the guidance of architect Andrea Moroni, who had already been the master builder of the basilica of Santa Giustina. Upon his death, the complex was finished by Andrea della Valle. The calm rhythm of its porticoes evokes the vanished grandeur of this place, that now attends silent and proud to the passage of time. In its harmonious shapes, however, it still echoes the spirit that leads the construction of the vast complex today in ruins.

The shape and structure of the Charterhouse, had to help the silence and the isolation of its inhabitants, to create the ideal conditions for them to get in touch with God. But in a Carthusian monastery, the solitude of the monk is balanced by a series of collective moments: like a small citadel, the Charterhouse hosts a community of hermits, in which the two great traditions of the oriental anchoritism and the western cenobitism meet. The extreme strictness of the Carthusian Order contributed to make them highly esteemed members of the Church. The Carthusians spend the most of their days in seclusion and prayer: they lodge separately in a series of cells where they pray, work and consume their meals in solitude. To ease the struggle of excessive praying, every cell is provided with a workshop space and a small private vegetable garden. For a Carthusian, communal-life moments are limited to the Sunday meal in the Refectory and to the gatherings in the Chapter House: monks meet daily in the church, but they don’t speak except for praying. Moreover, just one time per month, monks are allowed to exit the walls of the complex, into the territories of the «Désert de Chartreuse», the extended lands all around the building that keeps prying eyes away.

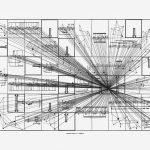

Maximum solitude is made possible by the work of the lay brothers. They lodge in a separate area of the complex and look after the sustenance and the autonomy of the community, from food preparation to the relations with the outside world. Separation between monks and lay brothers is absolute: even the Church and the Refectory are divided into two different spaces in order to prevent them from coming into contact with each other. The hermitic life of the monks, the cenobitic functions and those related to the work of the lay brothers are each identified with a cloister, thus constituting three different nuclei: the Great Cloister, which gathers the monk’s cells; the Little Cloister, which leads to the communal-life space and the economic courtyard, where the activities of the lay brothers take place, far from the cells in order not to disturb the silence of the Carthusians. The Church, ideal and spiritual centre of the complex, is the meeting point between the three different nuclei that compose the monastery.

After its foundation, the construction of the Charterhouse continued for over a century, but it was never completed: only one of the three sides of the Great Cloister, that had to be closed with the cells is ended; nevertheless, the small Carthusians and lay brothers’ community silently animated its spaces for over two centuries. In 1768, a decree of the Repubblica Veneta ratified the end of the Carthusian community. The complex remained abandoned for a few decades, until it was acquired by Count De Zigno, who embarked on a project for the transformation of the building into his country residence. One half of the church was demolished: the lay brothers’ half was kept as the family chapel. The side-chapels were also pulled down, the outline is still visible today on the bare side of the church. The building housing the refectory was destroyed in order to unify the two courtyards that flanked it; one of the cells was replaced by a Renaissance-styled portal, while another was enlarged to host the master’s apartment; the courtyards were renovated to house English gardens and the interiors were completely recast. The manufacturing spaces of the lay brothers were converted to house farming-related activities: the barchessa, for instance, was used for silkworm breeding. During the two World Wars, the majestic buildings of the monastery housed barracks and a military hospital, then a shelter for indigents, and it was even used as an armory during World War II.

Today the Charterhouse belongs to the heirs of De Zigno family and is in a state of neglect. The «desert» that used to surround it managed to preserve its isolation, even if it’s more and more undermined by the speculative building logic. The vastness of its spaces can now only be guessed through the fronds of the many trees that surround it and preserve its intimacy: even the annual visits have been suspended due to the precarious conditions of the buildings. The Charterhouse today lacks a specific function, and the search for solitude that guided its construction has turned into abandonment. Nonetheless, its simple and severe architecture, the Great Cloister with the succession of the cells, the serene rhythm of its porticos and, most of all, the silence that pervades its spaces, still speak to us of the majesty and beauty of this forgotten place.

All rights reserved to Marco Lumini (for the photographs) and Alberto Michielotto (for the article). 2019.

Leave a Reply