“Left to his own devices he couldn’t build a toaster. He could just about make a sandwich and that was it.”

Mostly Harmless, Douglas Adams, 1992

The Toaster Project is basically an attempt to build an electric toaster from scratch.

No, we’re not talking assembling pieces from kits , but actually beginning with mining the raw materials, from the ground up.

British Thomas Thwaites‘ ambitious project starts from digging from abandoned mines in UK (“mining no longer happens in the UK”), processing the materials at home and forming a product that you can buy new by Argos for £ 3.94.

“After some research I have determined that I will need the following materials to make a toaster. Copper, to make the pins of the electric plug, the cord, and internal wires. Iron to make the steel grilling apparatus, and the spring to pop up the toast. Nickel to make the heating element. Mica (a mineral a bit like slate) around which the heating element is wound, and of course plastic for the plug and cord insulation, and for the all important sleek looking casing. The first four of these materials are dug out of the ground, and plastic is derived from oil, which is generally sucked up through a hole.”

The toaster project, behind its rather humourous premises, serve as a vehicle to raise a theoretical investigation on industrialization, mass consumerism, sustainability and DIY culture.

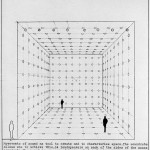

While the level of technology we can manage when we’re acting alone can’t pass the one of 15th century, extracting and processing materials happens in a scale irreconcilable with that of mass production.

“The contrast in scale between between consumer products we use in the home and the industry that produces them is I think absurd – massive industrial activity devoted to making objects which enable us, the consumer, to toast bread more efficiently. These items betray no trace of their providence.

So are toasters ridiculous? It depends on the scale at which you look. Looking close up, a desire (for toast) and the fulfilment of that desire is totally reasonable. Perhaps the majority of human activity can be reduced to a desire to make life more comfortable for ourselves, and has thus far led to being able to buy a toaster for £3.99 [among other achievements]. But looking at toasters in relation to global industry, at a moment in time when the effects of our industry are no longer trivial compared to the insignificant when our, they seem unreasonable. I think our position is ambiguous – the scale of industry involved in making a toaster [etc.] is ridiculous but at the same time the chain of discoveries and small technological developments that occurred along the way make it entirely reasonable.”

The Toaster Project is a on-going work you can read about in the artist site.

The installation at Ars Elec 2010 shows the attempts of recreating a working toaster, from melting minerals with air dryers and kitchenware, to creating the actual shape without moulds. The Thwaites model finally costs about £1187.54, but the process and the execution is priceless.

(Photos by Paolo Tonon, except the last one).

[…] the Toaster example, (see the last post), the physical attempt of building alone an otherwise mass produced object, seems to fail due to […]