This short, poetic article was originally published in the legendary magazine Terrazzo edited by Barbara Radice, in the very first number in 1988.

We thought it would be interesting to repropose it here on Socks along with the photographs taken by the author in India, that accompanied the writing on the same pages.

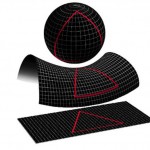

Those who designed the houses that I have photographed on my travels seem to me a bit like people that sail the open seas of architecture, people voyaging eastwards.

Ettore Sottsass (1988)

Travel Notes

Ettore Sottsass

(in: Terrazzo n°1, 1988)

In all the places I’ve been to I have felt that someone there was designing houses, just as in a wood you can feel the presence of mushrooms. In all the places I’ve been to I have felt or understood that somewhere round about someone was there designing houses, someone who desperately wanted to design and maybe also to build a house. Somehow, even if I was travelling around in a big hurry in some taxi to get about more quickly and even if I had — like an idiot — a camera hanging round my neck to look more quickly, it was clear that in every place there was someone designing houses: very careful people.

I naturally understood that these designers of houses were there hidden somewhere from the fact that there were houses and from the fact that the houses which I found were — in fact — designed and not just any house; they were not undesigned houses like the ones sometimes done by architects who are specialists and who sometimes don’t design houses but design speciality, in other words architecture…

I think that architects sometimes don’t design houses but ideas that can be had of how to design a house and then they design the ideas about how to design the ideas to be used to design a house, which is a bit like what happens to me here in India where I am at the moment, where they don’t leave me alone because everybody keeps telling me what to do to live happily: they tell me how I must eat, how I must breathe, how I must keep my back straight, they tell me when to go to bed, when to wake up and things like that and sometimes they also tell me how to address myself to the unknown.

All this to make me happy. Whereas I continue not to know how to live, but I do more or less live and I have to carry on, maybe unhappily, designing my life. Every now and again perhaps I do actually listen to these Indians, certainly I do. But I don’t know what their lives are like. I never tell them anything.

All this to say that there are times when architects — as specialists, as a special caste — collect ideas about architecture, a gigantic quantity of ideas and information about architecture and then this information is organized, published and communicated, interpreted, supported and then cataloged until eventually all this information and all these catalogs become tout court the actual existence of architecture itself; they become the place where architecture is confronted, the point from which measurements are taken; they become the manner itself, the manner of being understood, the cultural standard, trial and error etcetera.

At times also, all this information and all these catalogs become a certificate of caste, a tribal sign; sometimes even a national sign etcetera. At times I think that at the end of this journey, one may also find one has lost the best of the problem, I think that in the end one can lose that special feeling, that special hope, and most of all that reassuring aggressiveness, that determination without logic, that inebriating state, that can sometimes be experienced in designing and in building a house. It occurs to me that one may happen not to recapture, for example, that special state of innocence and curiosity, ignorance and conceit that one sometimes felt, as a child or later, when hiding under the stairs, entering an empty house, discovering a cave, building a hut in a tree, disappearing into a concrete pipe.

It occurs to me that one may even happen to forget that special more or less hidden zone represented by play: sometimes risky or angry or unhappy play and sometimes play that simply makes one laugh with orgasm, and sometimes play that with time becomes existential awareness, that becomes in other words rite, a long complicated, pointless, abstruse ritual with gestures and signs, with visions and depressions, with songs and meditations, with reasons and without reasons, with memories and inventions and not necessarily to be deposited on the Cambrian layer of history, but perhaps to be left to rise and disappear into the air, beyond the palm-leaves.

Then, of course, there are rituals of every description.

There are rituals to protect monetary status and there are rituals to assert the status of social power, there are rituals to show off, let us say intellectual-cultural status and there are rituals to show the status of a “life-style”, there are rituals for chasing time just as there are rituals for denying it, there are also rituals of methodological status, I mean rituals for protecting oneself during working hours and in the end there are complicated collages and very complicated mixtures of miscellaneous rituals in layers.

There are popular rituals too, rituals of people who know little or nothing about powerful social binders and who rely on signs, for what they are, for what they can give, who protect themselves with elementary rituals, with simple pújás that matter for what they are and for what they can give and nothing else.

It’s not so simple.

Perhaps the history of architecture may even no longer be that of Sir Banister Fletcher, into its eighteenth edition, or histories of that sort, I mean histories with catalogs of monuments, with catalogs of styles and descriptions of the works of art, when they are not histories done with the hierarchy of building heights or with lists of technological inventions or something.

Perhaps the history of architecture might some day or other also let its immense and immaculate bosom be kissed by some different child — I won’t say dissolute or irreverent, but only different, as my uncle Max was different from his eleven brothers and sisters who were the children of my grandfather and grandmother.

My uncle Max had simply disappeared and at home, apart from the odd legend, nothing more about him was known, the only thing left was a very faded and yellowish photograph of a young man wearing a cap and a melancholy expression leaning on a big boat on a misty beach somewhere, it was said, on the North Sea. My uncle Max was different: he had gone away along uncertain roads, perhaps also unknown, maybe even dangerous but where the air was probably inebriating, the skies infinite and where life could be a permanent curiosity, surprise, rapture. He had not stayed at Innsbruck to talk with the priests of the big churches to get commissions for baroque altars to be carved in wood, like the ones by my grandfather who was a sculptor of baroque altars. He hadn’t stayed with his carpenter brother to talk to the rich owners of hotels, restaurants and trattorie so that they would give him commissions for wooden doors, facings and furniture.

He had simply gone off across the open sea, who knows, maybe eastwards, to Bangkok, Yokohama or maybe even farther; this is not known. Evidently my uncle Max did not think of solving “the problem”; he probably didn’t even believe in “a solution”; my uncle Max did not even agree to play the game of those who are protected by others, who are protected by others, who are protected by others, ad infinitum; my uncle Max wasn’t even a sailor, because Innsbruck is perhaps the least marine place in the world, and so my uncle knew he would always be a dilettante and perhaps he never really learnt the proper names of things on ships nor the songs and maybe not even the swear-words; but in my opinion he did well: he disappeared leaving only legends and a heroic photograph.

Those who designed the houses that I have photographed on my travels seem to me a bit like people that sail the open seas of architecture, people voyaging eastwards.

All text and photos © Ettore Sottsass, Jr. © Archivio Ettore Sottsass.

[…] [Continuar leyendo (vía SOCKS)…] […]