German architect Oswald Mathias Ungers (1926–2007) accompanied his life-long architectural and theoretical production with a parallel work on found images which he would often compare to his own design proposals. Ungers collected and categorised found pictures as well as photographs of his own trips, and in 1982, he published a visual essay, introduced by a short text, called, Morphologie: City Metaphors. In the book, he conceptualised his procedure of design as a method guided by analogies and metaphors and explained how visual thinking operates. The introductory text, titled ‘Designing and Thinking in Images, Metaphors and Analogies’ had been previously published in 1976.

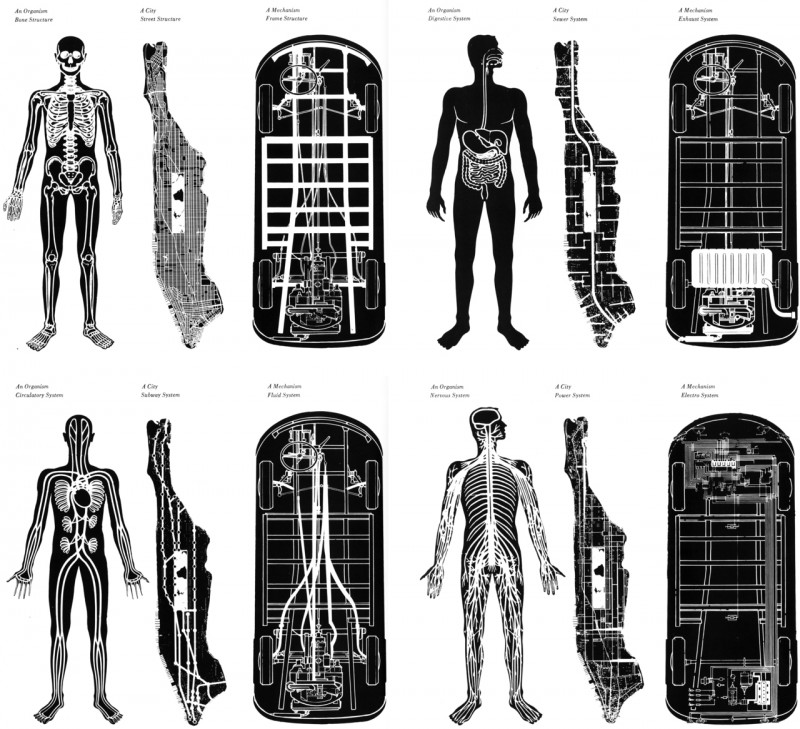

Throughout the whole book, Ungers set up a series of spreads where more than fifty city maps are each associated with a single picture mostly from the domains of science, biology and technology. The maps have different graphic qualities and range from plans of existing cities, like Venice or Timgad, to projected cities like Leonidov’s Magnitogorsk, ideal Renaissance cities and urban designs like Olmsted’s Riverside. The format stays always the same throughout the whole book, with a map on the left and another image on the right, both framed as squares, accompanied with a single word, in English on the left page and in German on the right one, as to synthetically describe the metaphor implied by each visual couple.

In the essay accompanying the book, Ungers inquires on the role of imagination in the construction of knowledg and argues that visual thinking is the most effective procedure to relate ideas to form.

The architect describes a mode of thinking, which he opposes to empiricism, in which the sense of sight is capable to relate together and “interpolate” ideas, by unifying them through a synthetic image. He does not claim that this approach could or should replace quantitative scientific studies but he states the necessity of counterbalancing the strict use of scientific procedures in the construction of understanding.

Imagination is described “as an instrument of thinking and analysing” and even the whole process of thinking is considered as an “application of imagination and ideas to a given set of facts.” Imagination gives birth to a “comprehensive vision” which allows one to make sense of reality. Without it, reality would only appear as an accumulation of equally important facts, impossible to make sense of.

As the meaning of a whole sentence is different from the meaning of the sum of single words, so is the creative vision and ability to grasp the characteristic unity of a set of facts, and not just to analyse them as something which is put together by single parts. The consciousness that catches the reality through sensuous perception and imagination is the real creative process because it achieves a higher degree of order than the simplistic method of testing, recording, proving and controlling.

Further in the text, Ungers ventures into the description of the imaginative process in relation to perception and psychology, to elaborate his theory of imagination as “a fundamental process of conceptualising an unrelated, diverse reality through the use of images, metaphors, analogies, models, signs, symbols and allegories.”

Only at the very end of the essay, he refers to the specific content of the book, to explain how the maps are presented not for their factual, measurable qualities, but for their metaphorical potential.

Therefore, the city-images as they are shown in this anthology are not analysed according to function and other measurable criteria – a method which is usually applied – but they are interpreted on a conceptual level demonstrating ideas, images, metaphors and analogies. The interpretations are conceived in a morphological sense, wide open to subjective speculation and transformation. The book shows the more transcendental aspect, the underlying perception that goes beyond the actual design.

A synthetic discourse is constructed by the three elements: the maps, the images which reveal the metaphorical reading, and the titles which explore the conceptual dimension emerging from the confrontation of the two visual elements.

Leave a Reply