Kenji Ekuan (1929 – 2015) was an industrial designer and a central figure in Japan’s Metabolist movement. The shock provoked by the sight of Hiroshima bombings (where he lost his father and his sister) persuaded him to become a creator of things:

When I stood in the ruins of the city after losing my father and sister to the bomb there, I was suddenly overcome by this sense of personal mission. In a world where there was nothing left at all, I felt the call of all things man-made. The burned out shell of a streetcar, an overturned truck, a half-melted bicycle… I felt like they were calling out to me, saying, “Hear us, O traveler!” (…) Experiences like that redirected my perception of the mutability of life from a sense of vanity and desolation to the sense that change drives new growth. I vowed to pursue the kind of change that fit the needs of postwar Japan through industrial design” (Excerpt from an interview of Rem Koolhaas and Hans Ulrich Obrist with Kenji Ekuan, in “Project Japan, Metabolist Talks”, Taschen 2011)

With a mixture of heroism and spirituality (arguably inherited from his late father, a Buddhist monk), Ekuan accomplished his life mission by designing “democratic” objects like public telephone booths, capsules, musical instruments and, – the one which he became famous for -, the Kikkoman soy sauce bottle. Less internationally known but equally as important are his contributions to the Metabolist project, (Kenji joined the group since the beginnings, at the 1960 World Design Conference), a series of interiors-, housing and mass produced designs and realisations questioning human inhabitation and ways of living. Determining to his education was the participation in Konrad Wachsmann’s Tokyo seminar in 1955, a decisive turning point in the younger architects’ awareness of technological possibilities, and the Buddha-like teachings of professor Iwataro Koike, to whom Ekuan and his fellows dedicated the name of their 1952-born design collective (GK – Group Koike).

After the 1953’s “Phone Booth” (a pre-capsule design that became ubiquitous in Japan) and the 1962-63’s “Plastic Ski Lodge” (a well equipped mobile home transportable on a truck), Ekuan began designing systems operating on every scale: from the single furniture to a city: “insisting“, as stated on “Project Japan” “on fluidity between object, architecture, and urbanism“.

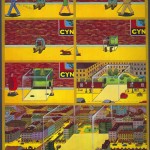

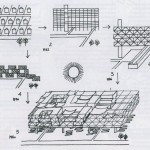

1964 “Furniture House” is the result of a series of experiments on the creation of domestic space through movable – Metabolist furniture – each one equipped with a structure of “skeleton”, “organs” and “skin”. The house is not defined by walls but by the composition of furniture, this way predating of almost ten years the experimentations of European and (above all) Italian radicals, as the pieces exhibited at 1972’s “Italy, the New Domestic Landscape” (also, here). (Cf. our articles on Sottsass‘s and Joe Colombo‘s furnitures domestic environments in Socks.)

Increasing the scale, in 1964 Ekuan designed the “Pumpkin House” as an expandable structure for a couple, able to feature outdoor space and even expandable to include a mini-capsule for a child.

1964’s “Tortoise House” is a family dwelling integrated into an inhabitable space frame formed by separated room-units and facilitating growth.

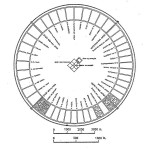

Again in 1964 (obviously, a very productive year for Ekuan), yet escalating in scale from the furniture to the megastructure, is the design for a “Dwelling City“, a double stacked tetrahedrons structure with capsules attached on the surface and the interior designated as public space. A primitive concept of “Cities within Cities” is obtained by the definition and mutliplications of clusters. The project was intended to be installed in the Kote area of Tokyo, frequently flooded.

Further reading:

Interview with Hall of Fame contributing writer Kenji Ekuan

Industrial designer Kenji Ekuan(1929 – 2015), on Kamiwaza

“Past Futures“, an article by Amelia Groom on Frieze

“Kenji Ekuan, Who Gave Soy Sauce Its Graceful Curves, Dies at 85“, Obituary with on the New York Times

Images mostly via: “Project Japan, Metabolist Talks”, Taschen 2011

Leave a Reply