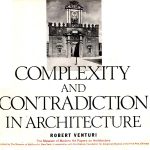

After proposing the last chapter of Complexity and Contradiction, we would like to publish here a rare text by recently passed away architect, historian and teacher Mario Manieri Elia, whose introductory course we had the privilege to attend ourselves while students.

The text has originally appeared in 2001 in a publication edited by the school of Architecture of Roma3 following an International Design Workshop to which Robert Venturi and Denise Scott-Brown were invited to teach, give speaches and exhibiting “recent” works.

Mario Manieri Elia

La storia della progettazione architettonica / The History of Architectural Design

in:

Continuità e discontinuità Vuoti urbani nel tessuto antico / Continuity and discontinuity Voids in the Urban Fabric

Seminario internazionale di progettazione / International Design Workshop

22 febbraio – 2 marzo 2001 / 22nd February – 2nd march 2001

a cura di / editors:

Cristiana Bedoni, Cristiana Marcosano dell’Erba, Maurizio Ranzi, Carolina Vaccaro.

Text translated by: Alexandra Z. Schmidt

—

Since our cultural repertoire highlights the History of Architecture, while the History of Architectural Design is almost unheard of we have to ask ourselves why that should be, in an environment so crowded with designers.

The answer lies in the fact that, within the traditional cultural climate, we make history of that which has a story. The story is recognizable in a Hegelian way as a great design, drawn — frontally and in profile — representing an ordered progression toward planned objectives and recognizable within its own rational completeness. However, modern historical study is now able to explain itself with regard to becoming and amongst an unpredictable and dynamic flow of events. The historian’s job is to recognize meaningful and describable processes within this flow. This presupposes interpretation: i.e. a process of hypothesis/verification that is derived. On the other hand, there is a focus on what we give sense to, within the broad semantic context. This means that the historical approach, combined with the design approach, as a dynamic concept, tend to converge within the vital practice of explaining historical reality. Therefore, from the modern analytical perspective, design tends to appear to us to be itself historical analysis, before becoming the ‘object’ of historical study.

But let’s attempt, with respect to the most classical historical method1, to begin at the origins, borrowing from introductory design lectures the primordial category of adaptation to a changing environment. Among the mechanisms humans have used to inhabit the world, the most important is language; communicative adaptation is active in humans right from birth, through sensory perception, up to perceiving and understanding objects of high semantic density and quality that we define as ‘art’. Artistic language, in fact — from dance to music to poetry, from decoration to figurative work to spatial construction — establishes meaningful and vital relations between humans and things: ephemeral and gestural in the first group and more stable and elaborate in the second group. In any case, inductive/deductive intentional processes are activated and they imply the ability to make symbols and to design. In particular, architectural design assumes a more vital perspective, in explaining our transformative role in the world; a role that implies capabilities for shared decision-making and the desire to create stable meanings. This STABILITY becomes the statute and the first ‘intention’ that architectural work (the conclusive result of the transitory phases dedicated to design) is destined to express. Due to the value given to stability, the dynamic but precarious quality of the temporary products of the design phase is inevitably excluded.

This oppositional separation between the work as a completed architectural product and design, as a path of knowledge and performance, is more apparent than the language that informs the work. It is openly directed towards a spatio-temporal rootedness that makes history “solid”, where human construction emerges as a fixed object, with the possibility of self-reference in the flux of becoming. This is the linguistic assertiveness of ancient classicism: from the Parthenon or the Coliseum; two topos that, not by chance, are the first images that the word ARCHITECTURE evokes. And one could say that architectural language, at least in the West, began and developed through the formation of a true intrinsic contradiction: that of a formative process that naturally places itself within becoming but which is conditioned by an expressive intentionality — that of stability and de-finition — which creates a barrier to becoming.

Porta Pia. The Classical in “Michelangelo Style” (Image from Robert Ventury, Complessità e contraddizioni nell’architertura, Dedalo, Bari 1980)

Porta Pia. The Classical in “Michelangelo Style” (Image from Robert Ventury, Complessità e contraddizioni nell’architertura, Dedalo, Bari 1980)

From the top: E.Munch, Nietzsche Portrait, Stockholm, Thielska Galleriet. P.Picasso, La fabrica de Horta de Ebro, 1909

From the top: E.Munch, Nietzsche Portrait, Stockholm, Thielska Galleriet. P.Picasso, La fabrica de Horta de Ebro, 1909

Between these two approaches — the first evolutive and the second anti-evolutive — the history of architecture maintains the operation of a reassuring choice, polarizing itself in the analysis of languages judged to be mature and de-finite; reluctant to take on an inevitably evolutive nature, both in a material and semantic sense, from the works chosen as milestones. Therefore, how could it deal with the adventurous theme of the history of design? It decided to push it to one side.

And here we are, on the other hand, ready to insist on centrality. In fact, it must be said that, in a truly contemporary conception consistent with the theoretical knowledge by now obtained in the cognitive sciences, the principal object of historical study is, and cannot not be, the state of becoming. Therefore, we focus on the evolutionary and process-oriented aspects of language, as an activity of knowledge and design; both in the broader sense — of which we spoke at the start of this text — and in a more specific sense, of architectural language and design language. Design work, not less than historical study, is placed within the definition of becoming, as a process of giving sense to something, formalized according to a linguistic tradition of meanings. It is enough to think of the classical ‘architectural orders’, whose canonic definition becomes the focus of the attention of Mediterranean and European societies and cultures for centuries. But despite this apparently consistent and determinant bi-millenary design of linguistic codification, historical study will still discover and value the implicit evolutive complexity and the cultural productivity of differences and of alternative languages produced through time. This explodes into the fervid linguistic babel of the avant-garde on the threshold of the twentieth century, when the dynamic of research stands (but only for a few decades) against any stabilized and institutionalized code.

At this point, there is a necessity to completely give way to a dynamic concept investing both the cognitive-critical approach and the cognitive-design approach to illustrate historical reality. The two readings are intertwined at the point of design itself progressing from an interpretation of reality, it tends to become to all intents and purposes ‘historical study’. Finally, the ‘History ofArchitectural Design’ will, in a certain sense, take on a meta-historical value: of the history of history. This is a complex and contradictory concept that, as has been said, traditional historiography has avoided as much as possible but which places itself as a decisive tool in understanding the relationship between humans and things, to work out and make fertile the operational relation between designers and becoming in the contemporary world.

Acquiring an understanding of the process of becoming implies a decisively design-oriented disposition, both as a deductive/inductive route of analysis/synthesis and as an intuitive short circuit, in reaching out into the space to be changed. However, the lack of solid traditional footholds and the risk of uncertainty often provokes a performance anxiety that returns us to the basic contradiction that contemporary architecture must con front. And anxiety, in turn, cannot not influence design.

Two types of design are prepared to face this risk — a mortal’ risk for architecture understood in the traditional sense — of uncertainty, after the great crisis of avant-garde growth: one representing flight from the feared instability of design, having recourse to the assertiveness of a strong and clear image; and the other — opposing the first but still with the same goal of exorcism — of acceptance and accentuation of uncertainty itself taken as a model of a confusion-generating dynamic. In the first group, there is the shooting star Le Corbusier, with his shining sunset of Chandigarh and the American response (also in India) of Louis Kahn; they propose a modern monumentality that, in the middle of the century, placed a few figurative cornerstones of great appeal. In the second category, we find the new hi-tech proposals of deconstructivist bent, signaled by the Japanese group Metamorph and re-launched by the English Archigram in the sixties.

Within this context, the awareness that Robert Venturi developed with his dissonant projects and his book Complexity and Contradiction in 1966, seems to take the ‘complexity’ of linguistic processes together with the basic ‘contradiction’ that supports modern architecture, within a phenomenological view and with surprising lucidity. With Venturi, who photographs the cultural situation and the difficult period for design in the last ten years, we are in the midst of that ‘dialogical’ relation with things to which Gadamer attributed the value of ‘hermeneutic truth’: a relation of feed-back in which the observer, whether historian or architect, enters into a two-way relation with the ‘thing’, “allowing the object to affect the observer”, after having presupposed and accepted alterity. And here design, entering into the world of objects, provides humans with a vital cognitive and interpretive tool. Gadamer understood this interactive dynamic between knowledge and trans formative intervention well when, beginning at Heidegger, he concludes limpidly with the incontrovertible phrase “Whoever wants to understand a text is carrying out a project’2.

This phrase can easily be reversed: “It is necessary to understand the text if one wants to carry out a project”. Understand means to select: the historic city provides the ‘text’ when we intervene in it and it cannot be reductively taken as a ‘pre-text’ for an improvised design product. It is rather a hyper-text, plural and confused, which sends a chorus of messages to our senses, flaunting themselves for our design scrutiny in their harmony and dissonance. This contextual overabundance includes concentrations and voids, rhapsodically assembled. It is possible to recognize flows of incredibly assertive and compact meaning, intersected and compromised among themselves, including unexpected and complex nodes of sense, polarized on the most meaningful historical traces and the principal locations of memory. In the end, the sense of the context emerges from all this, as an identifying overall value because of its controversial and mutable essence.

Notes

1

Gianni Vattimo, L’ermeneutica filosofica e la critica sulla probabilità della distanza, in “Figure” n.1, 1982, pp.52

2

Hans-Georg Gadamer, Sul circolo ermeneutico, in “Aut Aut”, 217-218, 1987, p.15. He then continues: “The understanding of that which is contained i the text lies in laying out the preliminary project, which will constantly be reviewed after further concentration of meaning.” (ibid.)”

Article saved!