MAP Office, a duo of artists and architects formed in 1996 by Laurent Gutierrez and Valerie Portefaix (already on Socks with their “Unreal Estates of China“) and based in Hong Kong, was one of the team selected to participate at the “Uneven Growth: Tactical Urbanisms for Expanding Megacities” exhibition, currently on-going at the MOMA New York (November 22, 2014–May 10, 2015) and organized by Pedro Gadanho, Curator, and Phoebe Springstubb, Curatorial Assistant, Department of Architecture and Design, The Museum of Modern Art.

Each group of multidisciplinary practitioners was asked to examine new architectural possibilities and develop proposals for six global metropolises: Hong Kong, Istanbul, Lagos, Mumbai, New York, and Rio de Janeiro during 14-months workshops.

The exhibition states that by 2030, the world’s population will be a staggering eight billion people and that two-thirds (mostly poor) will live in cities, and thus seeks “to challenge current assumptions about the relationships between formal and informal, bottom-up and top-down urban development, and to address potential changes in the roles architects and urban designers might assume vis-à-vis the increasing inequality of current urban development.”

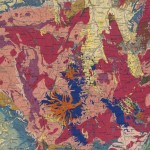

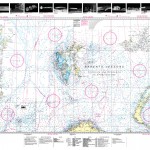

MAP Office’s work, entitled “Hong Kong Is Land” proposes adding eight artificial islands to the existing landscape of the city, which is already diffused across over 260 islands. If “cartography is a form of representation that often replaces the territory itself by imposing its own narrative upon it“, the project, according to the studio, aims to address “many urban population’s future needs while also providing distinctive hubs for tourism“.

Following its practice of working with maps and geographic diagrams, the duo produced a huge panel of drawings representing the eight new islands. For each one, they also provided an introductory text which appears below.

MAP Office contribution to Uneven Growth exhibition at the MOMA NY

Hong Kong Is Land

MAP Office

Swimming, floating, fleeing, sinking, how to absorb millions of climatic refugees?

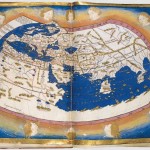

Artificial islands are territorial fragments. They are constructed and destructed in a cycle that involves many of the forces characterizing human civilization. This cycle of production and destruction is a means of escaping the present and imagining the future. Cartography is a form of representation that often replaces the territory itself by imposing its own narrative upon it.

The rise in sea level induced by climate change is gradually redrawing the geographic map of the world by altering coastlines and creating new lands. In this context, man-made islands offer a valuable alternative to support a sustainable urban expansion with new modes of living, working and entertaining. Islands are paradigms of the human condition of life. They exacerbate both the logic and the characteristic modes of production and consumption of urban spaces. Artificial lands also provide distinctive hubs for tourism. Yet they cannot be recognized as islands nor generate their own maritime zones.

Pressed between sea and mountains, Hong Kong appears seems like a chaotic, hybrid and colourful built crystallization with a specific density. Informed by a complex geography, here the idea of concentric growth or continuous spread is replaced by a non-linear development of hyper-dense cores coexisting with the natural landscape, which constitutes more than 75 percent of the total land area. Framed by the city of Shenzhen to the north and the South China Sea on its three other sides, Hong Kong – 60 percent of which is composed of bodies of water – is entirely surrounded by China. A collection of more than 250 islands, most of them inhabited, the territory is now under pressure from Beijing to absorb new areas of urban sprawl in order to accommodate a 50 percent increase of its current population of 7.2 million inhabitants. Due to its historical struggles and the stress placed on its land resources, Hong Kong’s geography is a narrative that has been defined and redefined time and again in response to changes in political intentions and social and economical shifts. In contrast to traditional urban-planning strategies, its form fluctuates in a conflicting appropriation of recognized land and sea.

With MAP Office’s recent project The Invisible Islands (2013), a new perspective on Hong Kong’s composite territory may have emerged in the idea of populating the sea. The consequences of the Anthropocene age and the rise in sea level induced by climate change have conspired to provide the opportunity to redraw the world’s geographical atlas by altering coastlines and creating new lands. Man-made islands are a valuable alternative to support a sustainable urban expansion with new modes of living, working, and entertaining. Islands are paradigms of the living condition and as such can exacerbate the logic and characteristics of existing modes of production and consumption of urban spaces. Artificial islands are territorial fragments, yet they are constructed and destructed in a cycle that concentrates many of the forces characterizing human civilization. This cycle of production and destruction is a way to escape the present and to project the future.

Myths, legends, stories, histories – as many narratives as possible are needed to define the contours of a new territory. In the case of our project Hong Kong Is Land (2014), the pleasure in constructing new maps and atlases knows no bounds. There are endless possibilities for negotiating the position of new islands within the existing landscape. Our imagined map of Hong Kong is the result of our research into and experience of the city over the last twenty years. First we developed our project Mapping Hong Kong (2000) by drawing upon narratives based on the analysis of various time-based, or temporal, densities. Using the city as a laboratory of ideas for the extended region, our publications HK LAB 1 (2002) and HK LAB 2 (2005) then further explored the territory in terms of its unique urban and architectural features.

Until 2047, Hong Kong must face many challenges generated by its unique condition as a Chinese city outside the borders of the motherland. Among these, the threat of exponential population growth is considered one of the greatest with regard to city’s future stability. Hong Kong’s limited land area restricts possible avenues of population growth to three options. The first is to reclaim more land from the water, and the second is to urbanize the city’s protected parks, both of which are proposals that Hong Kong’s citizens have long fought against. The third option is to create artificial islands in portions of the city’s territorial waters that have not yet been exploited. In this context, Hong Kong could serve as a laboratory for an island-generation project that could subsequently be extended to the Pearl River delta and further along the coastline of China.

The Hong Kong Is Land project proposes adding eight new artificial islands (over 500 m2) to the existing landscape of the city’s 263 islands. In this way, the project addresses many of the urban population’s future needs while also providing distinctive hubs for tourism. They would not, however, be recognized as sovereign islands or generate their own maritime zones. More than a response to an unbalanced geography, the following eight island scenarios can be interpreted as a new language through which to explore and promote universal values and novel ecosystems. At the heart of this project is the goal of using Hong Kong’s territorial waters as a testing ground for solutions that could prove useful in other parts of the world facing similar challenges.

The Island of Land

The Island of Land is a mobile territory on the quest to create a new region. As an in-between territory, both ephemeral and permanent, it is a land of empty shells shining in the sun. A traditional oyster-farming village, Lau Fau Shan has stretched its limits into Deep Bay over the 20th century, slowly reducing the gap between Shenzhen and Hong Kong. Escaping the urban zone of the New Territories, children have made this island a new playground. They have transformed tools into toys and routine into amusing ritual. By throwing oyster shells into the water, they have gradually built new land while playing. A landscape of delinquency where humidity reaches the climax of mugginess, this new territory stands alone in its tentative political and geographical response to the liquid border separating Hong Kong from Mainland China.

The Island of the Sea

Water is an essential source of life, and access to it is a basic human right. The Island of Sea is a living organism with the desire to merge an aqua-structure with a fishing community. Made of layered Asian vernacular architecture, the floating village has an organization that is directly inspired by the condition of its liquid environment. Here the economy of survival is found in water. The sea replaces the land in order to feed the resident community. Each house encompasses water in numerous ways. Ready to be relocated and deployed, the island’s aqua-culture offers the possibility of creating a new economy and new means of food production. Located directly under the house or at its sides, seaweed and fish form the fields that the polluted land has lost. In this sense, the Island of Sea proposes a new sustainable way of life for an ecologically precarious future.

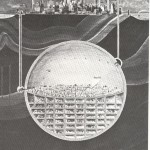

The Island of Self

The Island of Self is a floating territory made of an intricate, maze-like network of alleys. Constructed like a super-tanker, it is floating along Hong Kong’s invisible southern border in a no-man’s land where illegal consumption is authorized. With its tanks shaped in the form of buildings, the island is made up of an infinite network of pipes, wires and gutters that serve as the main organs feeding an intoxicated population. Dark and wet, the island’s labyrinth offers a hidden feast of drugs, adventure and sex. Here, passengers can experience a disconnected moment of time as the ship epitomizes the pleasure of being at the mercy of the sea. The island is also a stage for a youth-driven bacchanalia of excess.

The Island of Resources

The Island of Resources relies on the strong networking capability of the Filipino community outside its home country. Though the collection and distribution of basic resources, the island is a key element in assisting and comforting zones in the throes of emergency. Inspired by the form of a trading floor, it is a geometric organic structure characterized by a multifaceted complexity in the relationship between its inside and outside, its surfaces and volumes. At the island’s centre is a crater, a compact place sheltering the most precious resources, defending its coveted treasure like a giant safe. Located in the heart of Victoria Harbour, the floating island establishes a new form of trade in commodities and goods of all kinds to contribute to a new global economy of emergency.

The Islands of Possible Escape

An archipelago of hundreds of rocky mountains constitute the Islands of Possible Escape. Detached from the active world, these inhabited islands represent the hope for a possible recovery and reconstruction. Each island stages man-made nature in a perfect setting in which humans and animals live harmoniously in perfect self-sufficiency. Each island is self-sufficient, a miniature version of a perfect environment. Being located reasonably far from one another, they do not create any sense of neighbourhood or community. The most fascinating aspect of this voluntary isolation – not quarantine – is that it transforms an idyllic landscape into a theatre of permanent anxiety. To contain potential contamination by threat or conflict – such as a virus or other form of attack – each island takes the form of an independent platform; the only thing all of them share is the sky above them. The islands are antechambers of anticipation, places of fear in which to wait for something, somewhere that is about to happen. Here time is what offers stability, most of all through the offer of an escape from the anxiety and uncertainty of the things to come.

The Island of Surplus

The Island of Surplus in Junk Bay is an unstable archipelago made up of a complex accumulation and compression of various types of waste material. Bits of trash collide in an entropically generated landscape, creating an archipelago that can be interpreted from multiple points of view. Abandoned detritus built up over years of accretion resembles the prehistoric vestiges of an ignorant civilization. Yet the Island of Surplus is also one of the most visited ones in Victoria Harbour, with its unique silhouettes recalling Ha Long Bay. Its formerly booming business of recycling waste materials was once handled by hundreds of boats, but now there is only work enough for a few families. Appropriating the trash island, they transforms it into a fantastic laboratory for the manipulation of geology and geography. While the island’s grid structure supports these ephemeral constructions, the process of the accumulation of waste opens up unlimited possibilities. Metal, plastic and paper are arranged with the same compact rationale and are constantly relocated to the top of the island through the use of a single rotating crane. Trapping humidity and dirt, this new sediment quickly becomes a fertile terrain for various species of moss and plants, thereby proposing a new ecology of hope and life in a once heavily polluted territory.

The Island of Endemic Species

The conservation of biodiversity, the defence of endemic species and the control of leisure activities are what govern the protection of this island. The Island of Endemic Species is just a small ribbon of untouched land, yet it offers the opportunity to build a new ecosystem based on the migratory movements of plants and birds. With its limitless biological complexity, it is a jungle to explore for those who are willing to try coexisting with a wide range of living organisms. Here the separation of a territory from its population results in a new regulation of the ecology of life.

The Island of Memories

Islands can be laboratories for building new societies, but they can also preserve old ones. They are sometimes more intense or loaded than continental geographies. Mountains often embody the force and spirit of their initial formation, something still visible in their jagged peaks. They are the perfect location for finding life’s deeper meaning, for they are often held sacred and associated with many superstitious beliefs. The Island of Memories is shaped by our stories and serves as a continuous collector of our digital data – images, texts, passwords, etc. A person’s life is contained on a memory chip that is added to the top of the mountain. Through the addition of one chip after another, an archive is created through the construction of a sensitive portrait of a society in all its complex sociological, political and psychological manifestations. This accumulation of evidence – the stories of our lives – is methodically preserved in the infrastructure of the landscape, projecting our selves into the landscape. This is the collective memory of a world in search of a peaceful sanctuary.

Credits:

Project Directors: Laurent Gutierrez and Valérie Portefaix

Project Supervisor (Cartography): Gilles Vanderstocken

Project Manager (Film): Henry Temple

Project Assistants (Cartography): Jenny Choi Hoi Ki, Xavier Chow Wai Yin, Hugo Huang Jiawu, Venus Lung Yin Fei, Winson Man Ting Fung, Tammy Tang Chi Ching, Vivienne Yang Jiawei

Music (Film): Gilles Vanderstocken

Voice over (Film): Colin Fournier

Hong Kong Is Land is supported by the Design Trust and Hong Kong Arts Development Council

–

Hong Kong Is Land is exhibited at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

as part of Uneven Growth: Tactical Urbanisms for Expanding Megacities.

The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA)

Department of Architecture and Design

Address: 11 W 53rd St, New York, USA

Opening: November 19, 2014

Date: November 22, 2014–May 10, 2015

Curator: Pedro Gadanho

Assistant Curator: Phoebe Springstubb

[…] MAP Office: Hong Kong Is Land (2014) […]