Not much happens in A.M. Homes‘s short story “The Weather Outside Is Sunny and Bright“: the protagonist visits her Alzheimer’s mother, takes a bath, exercises her supernatural powers while working:

Architectural forensics is her field—why buildings do what they do. Often called upon as an expert witness she is known as “X-ray specs” for her ability to read the inanimate, to intuit what transformed it, to find the otherwise invisible marks of what happened and why. She is the one you want to call when there is a problem to solve—cracking, sinking, the seemingly inexplicable.

Yet, the story is eerily magic, as if magic realism met Alice Munro’s economy of style. In the tale, architecture is a metaphysical presence, a living subject that breaths and communicates. Walls are not inanimate: they stand, move and collapse; they haunt the woman: in her mind they can shape oppression and violence. As a matter of fact, she remembers when, as a child, she fell down a well…

Before leaving for work, in the morning, she recalls a dream:

“I dreamed the building was sealed, there were no doors, no windows, no way in or out, nothing to knock, nothing to ring, nothing to bang against,” she says. “The house of glass was suddenly all solid walls”.

We don’t know exactly why Anne Holtrop was fascinated by this short story (that he arguably read) so much he decided to entitle his diploma project at the Academie van Bouwkunst Amsterdam just like this last sentence, but we bet his three-parts study on the implications of walls on dwelling comes also from there: “Not just a delimiter, the wall also connects.” (Holtrop writes) “As Dutch architect Wim van den Bergh puts it: ‘You need a border to be able to unite.’ ”

Three types of walls are used as pretext for three dialectical experiments:

In “The single wall”, the first one, the wall acts as a one-sided delimiter, just like in Pompeii and in a project for three dwellings by Mies.

“The double wall” shows, instead, the wall’s connective quality and the creation of public space like in Piranesi’s Campo Marzio.

Finally, “The more than double wall”, the spatial conclusion, acts as the formal reversal of the second experiment: here, the structure is uninterrupted and the buildings are comparable to the poché and the interstitial is a figure-figure relationship.

In a final possible reference to AM Homes tale, Holtrop writes:

Each drawing shows not just the contours of the facade but also gives, in dotted lines, the position of the rooms and the thickness of the floors and walls. The drawings show not just the inner or outer side of the wall but its interior too. The wall is laid bare as in an X-ray photograph. (Excerpt from the introductory text. Read full text at the end of this post).

The rooms of a house can shut themselves off and relate to the court. This creates a second unit with the court as meeting place.

The rooms of a house can shut themselves off and relate to the court. This creates a second unit with the court as meeting place.

“The House of Glass Was Suddenly All Solid Walls”

(Anne Holtrop, 2006)

This architectural study into the wall and its relationship to dwelling takes the form of three experiments with a spatial conclusion. Not just a delimiter, the wall also connects. As Dutch architect Wim van den Bergh puts it: ‘You need a border to be able to unite.’

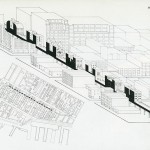

I have chosen to locate my experiments at an existing site in Amsterdam’s ‘Western garden suburbs’, where 30 dwelling units are to be realized in an area of 75 by 120 metres.

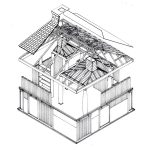

I distinguish between three types of wall in my research. In the first experiment, ‘the single wall’, the wall acts as a border of one-sided orientation. Key features of this experiment are Pompeii and a design for three dwellings about a courtyard by Mies van der Rohe. In both examples, several dwellings constitute a rectangular urban block, the dwellings there interlocking in an ingenious fashion. The border between them is not perfectly defined, its amorphous condition lending the design an element of ambiguity. This freedom in delimiting is taken to the greatest possible lengths, both between the individual dwellings and in the interior of each. The outcome is a block where every hierarchy among the dwellings has fallen away without compromising the quality of individual units.

In the ‘double wall’ it is the wall’s connective quality that features prominently. Examples of such walls are Piranesi’s Campo Marzio and Bernini’s Sant’Andrea alle Quirinale. In Campo Marzio, the grouping of buildings and the succession of walls seem to stitch public space and buildings together. This property of the wall underpins the second experiment. Here the configuration is one of freestanding houses with the outdoor space shaped by the amorphous residual areas between the houses. These areas are public, though there are places where openings in the facade and local widenings give the space the properties of a private zone.

The ‘more than double wall’ is a formal reversal of the second experiment. The dwellings present a single uninterrupted structure, the open spaces are local and enclosed. The dwellings or rather the mass can be compared to the poché, a black infill between two adjoining voids. In this case, Borromini’s San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane in Rome serves as a reference. Peter Eisenman contends that the qualities of the poché should be visible when this is seen as an interstitial space. The interstitial gives rise to a figure-figure relationship, as in a labyrinth, which simultaneously ties two spaces together and preserves their independence.

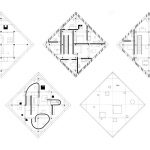

I have conducted the third experiment as a ‘spatial conclusion’ to the research. It consists of 33 dwellings enfolding 19 shared courts. Each court has several dwellings on it and each dwelling accesses more than one court. This means that residents have different neighbours for each court. Facade openings set opposite each other forge visual and physical relationships between the patios, whereas the doors in the dwelling see to it that the rooms become part of the adjoining court.

In the detailed design I have made the walls of the dwelling translucent so that there is no view through or reflection as with glass. The wall works as a projection plane on which shadows, shapes and subtle differences in colour can be perceived. There is a tension between settled and unsettling, between form and formless. So the interior is not simply bounded by the wall. Many boundaries can be perceived, as in a mysterious drawing by Adolf Loos for the Rufer House. Each drawing shows not just the contours of the facade but also gives, in dotted lines, the position of the rooms and the thickness of the floors and walls. The drawings show not just the inner or outer side of the wall but its interior too. The wall is laid bare as in an X-ray photograph.

Further reading:

2006 Dutch Archiprix project’s page

A.M.Homes. Things you should know: A collection of stories. Review here.

Leave a Reply