In 1789, during the Revolution and specifically during his imprisonment, architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux started the project for the “Ideal City of Chaux”. Twenty years before that time, in 1775-1778, the architect had designed and built the Royal Saltworks (Les Salines Royales) at Arc-et-Senans in the territory of the massive forest of Chaux, in the region of Franche-Comté, a complex of buildings which would become the starting point for the project of an utopian city.

At that time, as salt was an essential commodity (necessary for food preservation), it was subjected to a heavy taxation (known specifically as the gabelle). Collected by the Ferme Générale, the tax provided a valuable income for the French king.

In the region of Franche-Comté, salt was extracted from saline wells by vaporizing water within wood-fuelled furnaces. In Ledoux plan, the saline is located near the forest, in order to easily transport the wood, while the saline water was to be brought to the factory by the means of a new canal.

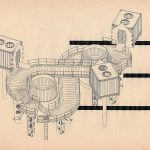

The built saline works are shaped in the form of a semicircular open air plan with ten functional buildings arranged along an arc and with the director’s house standing at the center. Other buildings host the cooper’s forge, the forging mill, the workshops for the extraction of salt and the administrative functions, while two other buildings host the workers’ houses. Each building has a public façade oriented toward the center, and a private one, where the workers’ bathrooms were located, connected to the vegetable gardens.

The main entrance of the site, at the axis of the semicircle, is marked by massive doric columns which frame the entrance of the director’s house from the distance. The language developed is a reinterpretation of the classical combined with elements completely invented by Ledoux to suit the industrial nature of the building, like the massive rusticated columns, and the references to local architecture in the form of rustic roofs. Several decorative solutions play allusion to the elements of water and salt, like the “petrified” water fountains on the walls or the cavernous hall which mimics an actual salt mine and is further ornated with concrete representations of the forces of nature and the organizing genius of Man. The royal saltworks closed in 1790 just after the French Revolution.

The Ideal City takes the plan of the saltworks as a central point for its development, embodying an idea of communal life joined to that of a new industrial urbanism. In the “Ideal city of Chaux” the semicircle becomes a circle and the ten buildings of the Saltworks are completed by many others. For each one of them, Ledoux set up a plan, explained their functioning and engraved an image. These documents were to be published afterward in his treaty of architecture, only partially completed in 1804.

The city featured a number of isolated buildings each one playing with symbolic elements. (The cemetery, the temple, the house of the farm guards, the farm buildings, etc…). The drawings appearing in L’architecture considérée sous le rapport de l’art, des moeurs et de la legislation, Tome 1, 1804, are both built projects related to the actual salt works and imaginary buildings in the general context of the Ideal City of Chaux.

Chaux saltworks. First Project.

All images from: Claude-Nicolas Ledoux, L’architecture considérée sous le rapport de l’art, des moeurs et de la legislation, Tome 1, 1804. (Retrieved on Gallica)

Extraordinary. What a work. Respect.