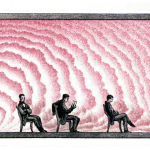

During his tenure as Professor of Perspective at the Royal Academy, (between 1807 and 1837) Joseph Mallord William Turner created 170 drawings, perspectives and diagrams in order to use them as visual aids for the lectures. Half of this material was assembled by the author before 1811 (Turner took over three years to prepare his lectures, researching a wide range of historic treatises as well as more contemporaneous sources) and subsequently improved, integrated or reworked until 1820. Altogether the diagrams depict a wide range of subjects related to both linear and atmospheric perspective. The author made use of a wide array of modes of presentation: from technical drawings to watercolours. To be visible, the drawings were particularly large: as much as two by three feet (about 60 x 90 cm), and installed upon adjustable supports.

The production of Turner’s diagrams must have been relatively straightforward. The majority of the drawings are completed in bold strokes of red and black watercolour over indications in pencil. These were usually done freehand, with only occasional use of straight edges. On most of them, Turner wrote the name of his source above or below the procedure delineated. There are a handful of more finished watercolours, however, for which he used a more complex transfer process. For these, Joyce Townsend, Senior Conservation Scientist at Tate, has determined that he placed a sheet of paper coated with lamp black under his original drawing and then traced over the outlines to generate a copy, or sometimes multiple copies. The fact that a number of the originals show indications of a transfer process on their reverse suggests that the transfer or copy paper was prepared, most likely by Turner himself, by dipping it in lamp black to coat both sides. Once he had his guiding lines, he finished the copy with watercolour. The Turner Bequest holds a few sheets of paper with unelaborated tracings. (Andrea Fredericksen, 2004).

The lectures were arranged as follows: the first one was “rather introductory than technical“. The second one dealt with more theoretical aspects as well as some problems of linear perspective. The third lecture was dedicated to themes of practical perspective, from an history of the techniques for drawings a cube and circular sheps to how to render the architectural orders. Lecture 4 was about further methods of linear perspective. Lecture 5, about reflections and their relationships to light and shade. Lecture 6, entitled ‘Backgrounds, Introduction of Architecture and Landscape’ dealt with landscape paintings and wasn’t provided with diagrams.

According to Andrea Fredericksen’s essay, Turner was delighted by teaching architectural representation, in the form of ancient, modern or even imaginary buildings or details. However, Turner also cautioned future architects in his audience against ‘designs of architecture [that] are but splendid drawings when destitute of practicability by an over-indulgence of fanciful combinations’, (Fredericksen, cit.) probably referring to Gandy (master of caprice and fantasy) and Giovan Battista Piranesi and his prisons.

Deterred by some criticism in regards to his delivery and pronunciation (Turner was an awkward speaker), the artist gradually failed to give lectures since 1813, stopping altogether after 1828, but renoncing officially only in 1837.

Here’s a small selections of the diagrams, via the very complete Tate section on William Turner’s “Royal Academy Perspective Lectures: Sketchbook, Diagrams and Related Material c.1809–28”.

All images © Tate Britain

Leave a Reply