Here, we propose on Socks the tenth and last chapter (excluding the “Works” section) of Robert Venturi’s Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, (1966), in which the author stresses the ability of complex and contradictory urban parts or individual buildings to form a certain tension able not only to foster multiple levels of interpretation, but also to form a greater unity based on the principle of inclusion. “An architecture that can simultaneously recognize contradictory levels should be able to admit the paradox of the whole fragment: the building which is a whole at one level and a fragment of a greater whole at another level” (p.104).

Robert Venturi, The Obligation Toward the Difficult Whole, in: Complexity and Contradiction in architecture, The Museum of Modern Art Papers on Architecture, 1966, 2nd. ed. 1977, p.88-105. Available at: https://monoskop.org/images/2/2f/Venturi_Robert_Complexity_and_Contradiction_in_Architecture_2nd_ed.pdf [Accessed 2016/11/05].

… Toledo [Ohio] was very beautiful.*

An architecture of complexity and accommodation does not forsake the whole. In fact, I have referred to a special obligation toward the whole because the whole is difficult to achieve. And I have emphasized the goal of unity rather than of simplification in an art “whose … truth [is] in its totality.” 45 It is the difficult unity through inclusion rather than the easy unity through exclusion. Gestalt psychology considers a perceptual whole the result of, and yet more than, the sum of its parts. The whole is dependent on the position, number, and inherent characteristics of the parts. A complex system in Herbert A. Simon’s definition includes “a large number of parts that interact in a non-simple way.” 46 The difficult whole in an architecture of complexity and contradiction includes multiplicity and diversity of elements in relationships that are inconsistent or among the weaker kinds perceptually.

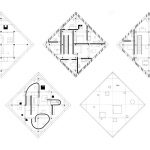

Concerning the positions of the parts, for instance, such an architecture encourages complex and contrapuntal rhythms over simple and single ones. The “difficult whole” can include a diversity of directions as well. Concerning the number of parts in a whole, the two extremes -a single part and a multiplicity of parts- read as wholes most easily: the single part is itself a unity; and extreme multiplicity reads like a unity through a tendency of the parts to change scale, and to be perceived as an overall pattern or texture. The next easiest whole is the trinity: three is the commonest number of compositional parts making a monumental unity in architecture. But an architecture of complexity and contradiction also embraces the “difficult” numbers of parts -the duality, and the medium degrees of multiplicity. If the program or structure dictates a combination of two elements within any of the varying scales of a building, this is an architecture which exploits the duality, and more or less resolves dualities into a whole. Our recent architecture has suppressed dualities. The loose composition of the whole used in the “binuclear plan” employed by some architects right after the Second World War, was only a partial exception to this rule. But our tendency to distort the program and to subvert the composition in order to disguise the duality is refuted by a tradition of accepted dualities, more or less resolved, at all scales of building and planning -from Gothic portals and Renaissance windows to the Mannerist façades of the sixteenth century and Wren’s complex of pavilions at Greenwich Hospital. In painting, duality has had a continuous tradition -for example, in compositions of the Madonna and Child and of the Annunciation; in enigmatic Mannerist compositions such as Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation (208); and in the recent work of Ellsworth Kelly (209), Morris Louis (210), and others.

Sullivan’s Farmers’ and Merchants’ Union Bank in Columbus, Wisconsin (211), is exceptional in our recent architecture. The difficult duality is prominent. The plan reflects the bisected inside space which accommodates the public and the clerks on different sides of the counter running perpendicular to the façade. On the outside the door and the window at grade reflect this duality: they are themselves bisected by the shafts above. But the shafts, in turn, divide the lintel into a unity of three with a dominant central panel. The arch above the lintel tends to reinforce duality because it springs from the center of a panel below, yet by its oneness and its dominant size it also resolves the duality made by the window and the door. The façade is composed of the play of diverse numbers of parts -single elements as well as those divided into two or three are almost equally prominent- but the façade as a whole makes a unity.

Gestalt psychology also shows that the nature of the parts, as well as their number and position, influences a perceptual whole and it also has made a further distinction: the degree of wholeness can vary. Parts can be more or less whole in themselves, or, to put it in another way, in greater or lesser degree they can be fragments of a greater whole. Properties of the part can be more or less articulated; properties of the whole can be more or less accented. In the complex compositions, a special obligation toward the whole encourages the fragmentary part or, as Trystan Edwards calls it, the term, “inflection.” 47

Inflection in architecture is the way in which the whole is implied by exploiting the nature of the individual parts, rather than their position or number. By inflecting toward something outside themselves, the parts contain their own linkage: inflected parts are more integral with the whole than are uninflected parts. Inflection is a means of distinguishing diverse parts while implying continuity. It involves the art of the fragment. The valid fragment is economical because it implies richness and meaning beyond itself. Inflection can also be used to achieve suspense, an element possible in large sequential complexes. The inflected element can be called a partial-functioning element in contrast to the double-functioning element. In terms of perception it is dependent on something outside itself, and in whose direction it inflects. It is a directional form corresponding to directional space. The interior of the church of the Madonna del Calcinaio in Cortona (137) is composed of a limited number of elements which are uninflected. Its windows and niches (212), pilasters and pediments, and the articulated elements of its altar, are independent wholes, simple in themselves and symmetrical in form and position. They add up to a greater whole. The interior of the pilgrimage church at Birnau in Bavaria (213), however, contains a diversity of inflections directed toward the altar. The complex curves of the vaults and arches, even the distortions of the pilaster capitals, inflect toward this center. The statues and the multitude of fragmental elements of the side altars (214) are inflected parts, asymmetrical in form yet symmetrical in position, which integrate into a symmetrical whole. This subordination of parts corresponds to Wölfflin’s “unified unity” of the Baroque -which he contrasts with the “multiple unity” of the Renaissance. A comparison of the entrance fronts of Blenheim Palace (215) and Holkham Hall (216) illustrates the use of inflection on the exterior. Holkham Hall achieves an extensive whole through the addition of similar wholes which are always independent: most of its bays are pedimented pavilions which could stand alone as single buildings -Holkham Hall could almost be three buildings in a row. Blenheim achieves a complex whole through fragmental parts, separate but inflected. The last two bays of the central block, when taken alone, are dualities incomplete in themselves. But in relation to the whole they become inflected terminations to the central pavilion, and a confirmation of the pedimented center of the whole composition. The piers at the corners of the porch and the broken pediments above them are also terminal inflections, similarly reinforcing the center. The bays at the far extremities of this enormous façade form pavilions which are not inflected. They are perhaps expressive of the relative independence of the kitchen and stable wings. Vanbrugh’s method of creating a strong whole in such a large and diverse if symmetrical façade follows the traditional Jacobean method of the century before: at Aston Hall (217) the wings of the forecourt façade and the towers, parapeted pediments, and windows inflect in position and/or shape toward its center.

The varying configurations of the wings and windows, roofs and ornaments of the orphanage of the Buon Pastore near Rome (218, 219, 220) are an orgy of inflections of enormous scope similar to the scale of Blenheim. This neo Baroque complex by Armando Brazini, (bizarre in 1940 and admittedly questionable for an asylum for little girls) astonishingly composes a multitude of diverse parts into a difficult whole. At all levels of scale it is an example of inflections within inflections successively directed toward different centers -toward the short façade in the front, or the anticlimactically small dome near the center of the complex, with its unusually big cupola. When you stand close enough to see a smaller element of inflection, you sometimes need to turn almost 180 degrees to see its counterpart at a great distance. An element of suspense is introduced when you move around the enormous building. You are aware of elements related by inflection to elements already, seen or not yet seen, like the unraveling of a symphony. As a fragment in plan and elevation, the asymmetrical composition of each wing is wrought with tensions and implications concerning the symmetrical whole.

At the scale of the town, inflection can come from the position of elements which are in themselves uninflected. In the Piazza del Popolo (221) the domes of the twin churches confirm each building as a separate whole, but their single towers, symmetrical themselves, become inflective because of their asymmetrical positions on each church. In the context of the piazza each building is a fragment of a greater whole and a part of a gateway to the Corso. At the smaller scale of Palladio’s Villa Zeno (222) the asymmetrical positions of the symmetrical arched openings cause the end pavilions to inflect toward the center, thus enforcing the symmetry of the whole composition. This kind of inflection of asymmetrical ornament within a symmetrical whole is a dominant motif in Rococo architecture. For example, on the side altars at Birnau (214), and on the characteristic pairs of sconces (223), or andirons, doors, or other elements, the inflection of the rocaille is part of an asymmetry within a larger symmetry that exaggerates the unity yet creates a tension in the whole.

Direction is a means of inflection in the Villa Aldobrandini (224). Its front is articulated into additive parts or bays, but the unique diagonals of the fragmentary pediments on the end bays tend to direct the ends toward the center, and unify that dominating façade. In the plan of Monticello (225) the enclosing diagonal walls inflect the extremities toward the center focus. In Siena the distortion of its façade inflects the Palazzo Pubblico (226) toward its dominating piazza. Here distortion is a method of confirming the whole rather than of breaking it, as in the case of contradiction accommodated. Baroque details, such as coupled pilasters in the end bays of a series of pilastered bays, become devices of inflection because they create variations in rhythm to terminate a sequence. Such methods of inflection are largely used to confirm the whole -and since monumentality involves a strong expression of the whole, as well as a certain kind of scale, inflection becomes a device of monumentality as well.

Inflection accommodates the difficult whole of a duality as well as the easier complex whole. It is a way of resolving a duality. The inflecting towers on the twin churches on the Piazza del Popolo resolve the duality by implying that the center of the whole composition is located in the space of the bisecting Corso. In Wren’s Royal Hospital at Greenwich (227) the inflection of the domes by their asymmetrical position similarly resolves the duality of the enormous masses flanking the Queen’s House. Their inflection further enhances the centrality and importance of this diminutive building. The unresolved dualities of the end pavilions facing the river, on the other hand, reinforce the unifying quality of the central axis by their own contrasting disunity.

The French chevet contrasts with the blunt termination of the English Gothic choir, because it inflects to terminate and enhance the whole. In the church of the Jacobins in Toulouse (228) the inflection of the chevet tends to resolve the duality of the nave, which is bisected by the row of columns. The apse in Furness’ library at the University of Pennsylvania similarly resolves the duality formed by the arched interior wall opposite. One column bisects the nave at the end of the Late Gothic parish church at Dingolfing (229), a hall-type church, but the juxtaposition of the central bay and window behind, which evolve from the complex vaulting above, resolve the original duality. The directional inflecting of the side walls of the nave of the parish church in Rimella (230) counteracts the disunifying effect of the two bays of the nave. Their inflection toward the center increases enclosure and strengthens the whole. A minor intermediate bay also binds the major bays together.

Lutyens’ work abounds in dualities. The duality of the entrance façade of the castle at Lambay (231), for instance, is resolved by the inflecting shape of the opening in the juxtaposed garden wall. In contemporary architecture rare examples of inflection are found in the vestigial broken pediments of Moretti’s apartment house on the Via Parioli (10). They partially resolve the duality of the pair of wings which distinguish sets of apartments. The subtly balanced duality of Wright’s Unity Temple (232) is devoid of inflections unless the directional entrance pedestal is one.

Modern architecture tends to reject inflection at all levels of scale. In the Tugendhat House no inflecting capital compromises the purity of the column’s form, although the shear forces in the supported roof plane must thus be ignored. Walls are inflected neither by bases nor cornices nor by structural reinforcements, such as quoins, at corners. Mies’ pavilions are as independent as Greek temples; Wright’s wings are interdependent but interlocked rather than independent and inflected. However, Wright, in accommodating his rural buildings to their particular sites, has recognized inflection at the scale of the whole building. For example, Fallingwater is incomplete without its context -it is a fragment of its natural setting which forms the greater whole. Away from its setting it would have no meaning.

If inflection can occur at many scales -from a detail of a building to a whole building- it can contain varying degrees of intensity as well. Moderate degrees of inflection have a kind of implied continuity that affirms the whole. Extreme inflection literally becomes continuity. Today we emphasize our opportunities to express the literal continuities of structure and materials -such as the welded joint, skin structures, and reinforced concrete. Except for the flush joint of early Modern architecture, implied continuity is rare. The shadow joint of Mies’ vocabulary tends to exaggerate separation. And Wright, especially, articulates a joint by a change in profile when there is a change in material -an expressive manifestation of the nature of materials in Organic architecture. But a contrast between expressive continuity and real discontinuity of structure and materials is a characteristic of the façade of Saarinen’s dormitory at the University of Pennsylvania. In section its continuous curves defy the changes in materials, structure, and use. In the precise walls of Machu Picchu (233) the same profile continues between the built-up jointed masonry and the rock in situ. The arched shape of the opening of Ledoux’s entrance at Bourneville (58) spans two kinds of structure (corbeled and arched) and two kinds of material (rusticated masonry at the top and smooth masonry at the bottom). Similar contradictions occur in Rococo furniture. Cabriole legs (234) disguise the joint and express continuity in their shape and ornament. The continuous grooves common to the leg and the seat-frame imply a continuity beyond inflection which is somewhat contradictory to the material and the structural relationship of these separate frame elements. The ubiquitous rocaille is another ornamental device for expressive continuity common to the architecture and furniture of the Rococo. Some of Wright’s early interiors (235) parallel in the motif of the wood strip the rocaille-filled interiors of the Rococo (236). In Unity Temple and the Evans House (235) these strips are used on the furniture, walls, ceilings, light fixtures, and window mullions, and the pattern is repeated on the rugs. As in the Rococo, a continuous motif is used to achieve a strong whole expressive of what Wright called plasticity. He employed a method of implied continuity for valid expressive reasons, and in ironic contradiction to his dogma of the nature of materials and his expressed hatred of the Rococo. On the other hand, an architecture of complexity and contradiction can acknowledge an expressive discontinuity, which belies a certain structural continuity. In the choir screen in the cathedral at Modena (237), where one uninflected element precariously supports another in its visual expression, or in the abrupt abutments of the uninflected wings of All Saints Church, Margaret Street (93), a formal discontinuity is implied where there is a structural continuity. Soane’s Gate at Langley Park (238) is made up of three architectural elements totally uninflected and independent; besides the dominance of the middle element, it is the sculptural elements which are inflected and which give unity to the three parts.

The Doric order (239) works a complex balance among extremes of both expressive and structural continuities and discontinuities. The architrave, the capital, and the shaft are noncontinuous structurally but only partially noncontinuous expressively. That the architrave sits on the capital is expressed by the uninflected abacus. But the echinus in relation to the shaft expresses structural continuity consistent with expressive continuity. The horizontal and vertical elements of Saarinen’s T.W.A. Terminal and Frederick Kiesler’s Endless House are without structural contradiction: they are continuous everywhere. However, precast concrete that is assembled offers ambiguous combinations of continuity and discontinuity, both structural and expressive. The surfaces of the Police Administration Building in Philadelphia include patterns of shadow joints separating precast elements whose curving inflections, however, evolve continuous profiles -a paradoxical play of continuity and discontinuity inherent in the expression and the structure of the architecture.

A kind of implied continuity or inflection is inherent in Maki’s “group form.” This, the third category in the designation of complex architecture he calls “collective form,” includes “generative” parts with their own “linkage,” and wholes in which the system and unit are integral. He has referred to other characteristics of group form which indicate some of the implications of inflection in architecture. A consistency of the basic parts and their sequential relationship permit a growth in time, a consistency of human scale, and a sensitivity to the particular topography of the complex.

The “group form” contrasts with Maki’s other basic category, the “mega-form.” The whole, which is dominated by hierarchical relationships of parts rather than by the inherent inflective nature of the parts, can also be a characteristic of complex architecture. Hierarchy is implicit in an architecture of many levels of meaning. It involves configurations of configurations -the interrelationships of several orders of varying strengths to achieve a complex whole. In the plan of Christ Church, Spitalfields (240), it is the sequence of orders of supports -higher, lower, and middle; large, small, and medium- that make the hierarchical whole. Or in a palace façade of Palladio (48), it is the juxtapositions and adjacencies of parts (pilasters, windows, and mouldings) and the contrasts of large, small, and relatively important that conduct the eye to the whole.

The dominant binder is another manifestation of the hierarchical relationships of parts. It manifests itself in the consistent pattern (the thematic kind of order) as well as by being the dominant element. This is not a difficult whole to achieve. In the context of an architecture of contradiction it can be a doubtful panacea, like the fallen snow which unifies a chaotic landscape. At a scale of the town in the Medieval period it is the wall or castle which is the dominant element. In the Baroque it is the axis of the street against which minor diversities play. (In Paris the rigid axis is confirmed by cornice heights, while in Rome the axis tends to zigzag and is punctuated by connecting piazzas with obelisks.) The axial binder in Baroque planning sometimes reflects a program devised by an autocracy, which could easily exclude elements that today must be considered. Arterial circulation can be a dominant device in contemporary urban planning. In fact, in the program the consistent binder is most often represented by circulation, and in construction the consistent binder is usually the major order of structure. It is an important device of Kahn’s viaduct architecture and Tange’s – collective forms for Tokyo. The dominant binder is an expediency in renovations. James Ackerman has referred to Michelangelo’s predilection for “symmetrical juxtaposition of diagonal accents in plan and elevation” in his design for St. Peter’s, which was essentially a renovation of earlier construction. “By using diagonal wall-masses to fuse together the arms of the cross, Michelangelo was able to give St. Peter’s a unity that earlier designs “lacked.” 48

The dominant binder, as a third element connecting a duality, is a less difficult way of resolving a duality than inflection. For example, the big arch unambiguously resolves the duality of the double window of the Florentine Renaissance palazzo. The façade of the double church of S. Antonio and S. Brigida by Fuga (241) is resolved by inflected broken pediments -but also by a third ornamental element, which dominates the middle. Similarly, the façade of S. Maria della Spina, Pisa (242) is dominated by a third pediment. In plan the domed bays of Guarini’s church of the Immaculate Conception in Turin (14) are inflected in shape, but they are also resolved by a minor intermediate bay. The ornamental pediment at the center of the elevation of Charleval (243) is also a dominant third element, as are the gable and the stair at the front of the farmer’s house near Chieti (244) -similar, in this context, to the function of the stair to the entrance of Stratford Hall, Virginia (245). There is no inflection in the composition of the Villa Lante (246), but an axis between the two equal pavilions, which focuses on a sculpture placed at a cross-axis, dominates the twin pavilions as a third element, thus emphasizing a whole.

But a more ambiguously hierarchical relationship of uninflected parts creates a more difficult perceptual whole. Such a whole is composed of equal combinations of parts. While the idea of equal combinations is related to the phenomenon both-and, and many examples apply to both ideas, both-and refers more specifically to contradiction in architecture, while equal combinations refer more to unity. With equal combinations the whole does not depend on inflection, or the easier relationships of the dominant binder, or motival consistency. For example, in the Porta Pia (110, 111) the number of each kind of element in the composition of the door and the wall is almost equal -no one element dominates. The varieties of shapes (rectangular, square, triangular, segmental, and round) being almost equal, the predominance of any one shape is also precluded, and the equal varieties of directions (vertical, horizontal, diagonal, and curving) have the same effect. There is similarly an equal diversity in the size of the elements. The equal combinations of parts achieve a whole through superimposition and symmetry rather than through dominance and hierarchy.

The window above Sullivan’s portal in the Merchants’ National Bank in Grinnell, Iowa (112), is almost identical to the Porta Pia in its juxtaposition of an equal number of round, square and diamond-shaped frames of equal size. The diverse combinations of number analyzed in his Columbia Bank façade (groups of elements involving one, two, and three parts) have almost equal value in the composition. However, there the unity is based upon the relation of horizontal layers rather than on superimposition. The Auditorium (104) exploits the complexity of directions and rhythms that such a program can yield. The simple semicircles of the wall ornament, structure, and segmental ceiling coves counteract, in plan and section, the complex curves of the proscenium arches, rows of seats, balcony slopes, boxes, and column brackets. These, in turn, play against the rectangular relationships of ceilings, walls, and columns.

This sense of the equivocal in much of Sullivan’s work (at least where the program is more complex than that of a skyscraper) points up another contrast between him and Wright. Wright would seldom express the contradiction inherent in equal combinations. Instead, he resolved all sizes and shapes into a motival order -a single predominant order of circles or rectangles or diagonals. The Vigo Schmidt House project is a consistent pattern of triangles, the Ralph Jester House of circles, and the Paul Hanna House of hexagons. Equal combinations are used to achieve a whole in Aalto’s complex Cultural Center at Wolfsburg (78). He does not disperse the parts nor make them similar as Mies does at I.I.T. As I have pointed out before, he achieves a whole by combining an almost equal number of diagonal and rectangular elements. S. Maria delle Grazie in Milan (247) works equal combinations into an extreme form by contrasting opposite shapes in its exterior composition. The dominant triangle-rectangle composition in the front combines with the dominant circle-square composition in the back. Michelucci’s church of the Autostrada (4), like the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem (plan only illustrated in 101), consists of almost equal combinations of contrasting directions and rhythms in columns, piers, walls, and roofs. A similar composition is that of the Berlin Philharmonic Hall (248). The plastic forms of indigenous Mediterranean architecture (249) are simple in texture, but rectangles, diagonals, and segments are blatantly combined. Gaudi’s dressing table in the Casa Güell (250) represents an orgy of contrasting dualities of form: extreme inflection and continuity are combined with violent adjacencies and discontinuities, complex and simple curves, rectangles and diagonals, contrasting materials, symmetry and asymmetry, in order to accommodate a multiplicity of functions in one whole. At the scale of furniture, the prevalent sense of the equivocal is expressed in the chair illustrated in (103). Its back configuration is curving and its front is rectangular. It is not dissimilar in its difficult composition to Aalto’s bentwood chair illustrated in (251).

Inherent in an architecture of opposites is the inclusive whole. The unity of the interior of the Imatra church or the complex at Wolfsburg is achieved not through suppression or exclusion but through the dramatic inclusion of contradictory or circumstantial parts. Aalto’s architecture acknowledges the difficult and subtle conditions of program, while “serene” architecture, on the other hand, works simplifications.

However, the obligation toward the whole in an architecture of complexitv and contradiction does not preclude the building which is unresolved. Poets and playwrights acknowledge dilemmas without solutions. The validity of the questions and vividness of the meaning are what make their works art more than philosophy. A goal of poetry can be unity of expression over resolution of content. Contemporary sculpture is often fragmentary, and today we appreciate Michelangelo’s unfinished Pietas more than his early work, because their content is suggested, their expression more immediate. and their forms are completed bevond themselves. A building can also be more or less incomplete in the expression of its program and its form.

The Gothic cathedral, like Beauvais, for instance, of which only the enormous choir was built, is frequently unfinished in relation to its program, yet it is complete in the effect of its form because of the motival consistency of its many parts. The complex program which is a process,continually changing and growing in time yet at each stage at some level related to a whole, should be recognized as essential at the scale of city planning. The incomplete program is valid for a complex single building as well.

Each of the fragmental twin churches on the Piazza del Popolo, however, is complete at the level of program but incomplete in the expression of form. The uniquely asymmetrically placed tower, as we have seen, inflects each building toward a greater whole outside itself. The very complex building, which in its open form is incomplete, in itself relates to Maki’s “group form;” it is the antithesis of the “perfect single building” 49 or the closed pavilion. As a fragment of a greater whole in a greater context this kind of building relates again to the scope of city planning as a means of increasing the unity of the complex whole. An architecture that can simultaneously recognize contradictory levels should be able to admit the paradox of the whole fragment: the building which is a whole at one level and a fragment of a greater whole at another level.

In God’s Own Junkyard Peter Blake has compared the chaos of commercial Main Street with the orderliness of the University of Virginia (252, 253). Besides the irrelevancy of the comparison, is not Main Street almost all right? Indeed, is not the commercial strip of a Route 66 almost all right? As I have said, our question is: what slight twist of context will make them all right? Perhaps more signs more contained. Illustrations in God’s Own Junkyard of Times Square and roadtown are compared with illustrations of New England villages and arcadian countrysides. But the pictures in this book that are supposed to be bad are often good. The seemingly chaotic juxtapositions of honky-tonk elements express an intriguing kind of vitality and validity, and they produce an unexpected approach to unity as well.

It is true that an ironic interpretation such as this results partly from the change in scale of the subject matter in photographic form and the change in context within the frames of the photographs. But in some of these compositions there is an inherent sense of unity not far from the surface. It is not the obvious or easy unity derived from the dominant binder or the motival order of simpler, less contradictory compositions, but that derived from a complex and illusive order of the difficult whole. It is the taut composition which contains contrapuntal relationships, equal combinations, inflected fragments, and acknowledged dualities. It is the unity which “maintains, but only just maintains, a control over the clashing elements which compose it. Chaos is very near; its nearness, but its avoidance, gives… force.” 50 In the validly complex building or cityscape, the eye does not want to be too easily or too quickly satisfied in its search for unity within a whole.

Some of the vivid lessons of Pop Art, involving contradictions of scale and context, should have awakened architects from prim dreams of pure order, which, unfortunately, are imposed in the easy Gestalt unities of the urban renewal projects of establishment Modern architecture and yet, fortunately are really impossible to achieve at any great scope. And it is perhaps from the everyday landscape, vulgar and disdained, that we can draw the complex and contradictory order that is valid and vital for our architecture as an urbanistic whole.

Notes

*

Gertrude Stein, Gertrude Stein’s America, Gilbert A. Harrison, ed., Robert B. Luce Inc., Washington, D. C., 1965.

45

Heckscher, op. cit.; p. 287.

46

Herbert A. Simon: in Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 106, no. 6, December 12, 1762; p. 468.

47

Arthur Trystan Edwards: Architectural Style, Faber and Gwyer, London, 1926; ch. 111.

48

Ackerman, op. cit.; p. 138.

49

Fumihiko Maki: Investigations in Collective Form, Special Publication No. 2, Washington University, St. Louis, 1964; p. 5.

50

Heckscher, op. cit.; p. 289.

I.ve loved that book!